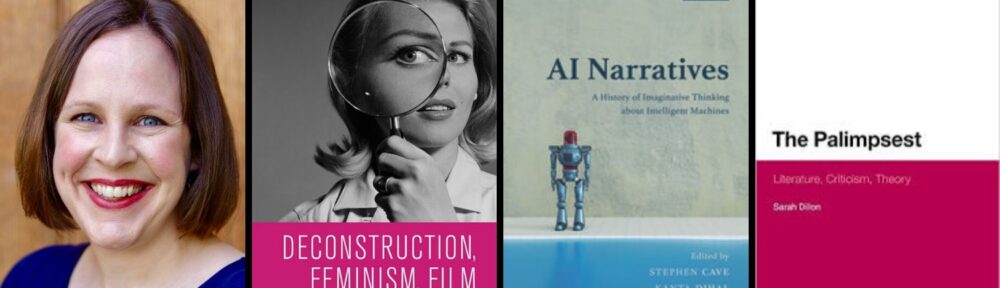

Before he became famous as the founder of modern structural linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure had this crazy side project looking for anagrams hidden in Latinate poetry, during which time the more he looked for connections, the more he found them. Saussure eventually abandoned the project but there’s a great book by Jean Starobinski called Words Upon Words that presents Saussure’s early research and recounts the story of his obsession. I came across it a long time ago when working on my PhD – and I discuss it in one of the chapters of my first book, The Palimpsest – but it always comes to mind again when unexpected connections present themselves to me. It always makes me wonder, as Saussure did, whether the connections are really there, or whether they are only there because I’m creating them. Over the years, I’ve become convinced that most frequently it is the latter – the connections only exist because you create them. But rather than this predicament leading me to question my sanity, I’m now convinced that this fortuitous and unanticipated connectivity is in fact the lifeblood of intellectual enquiry and, in fact, of any other form of creativity.

What’s prompted me to remember Saussure and his anagrams this week is an invitation I received from BBC Radio 3’s Free Thinking to go on the programme to talk to Rana Mitter, along with Laurie Sansom, about Muriel Spark’s The Driver’s Seat and Laurie’s new adaptation of it for the Scottish National Theatre. Having just reread The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for my Open Book Close Reading series, it was a pleasure to be prompted to reread another Spark text that I first read in the dim and distant past. It’s a weird and disturbing novella, with a dark side that far exceeds the sinister manipulations of Miss Brodie. Laurie Sansom says that he was prompted to develop the first stage adaptation because it seemed essentially dramatic. And he’s absolutely right: so much of the prose in fact reads like stage directions. This is a novella about setting, actions, and objects, with a third person narrator that knows what happens in the future but has no access at all to what’s inside the female protagonist Lise’s head. As we were talking on the programme, it occurred to me what a radically but problematically feminist text this is – it’s a biting satire on the conventional tropes of woman as victim. It eschews the immersion in psychological complexity of classic texts of female madness such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper. But the control she takes of her own fate – she seeks out and orchestrates her own murder – does not extend to an ability to control her sexual violation. Only through luck does she escape from two attempted rapes, and the man she has selected as her killer rapes her as well, despite her express wishes that his violation remain purely murderous, not sexual. We never find out what’s going on in Lise’s head, and that’s the point – that’s what renders her powerful rather than vulnerable; orchestrator rather than victim. But that power is also continually threatened by the unavoidable vulnerability of her female body. Which makes this a text about women and our bodies – to what extent we can control them and to what extent, whatever the defences we put in place with regard to our minds, we remain vulnerable in our embodiment.

Which leads to the unexpected connection. Giuseppe Patroni Griffi’s 1974 film adaptation of Spark’s novel adheres remarkably closely to the literary original. But it adds a curious uncanny touch in the opening scene – Lise is trying on a dress in a shop, as in the book, but in the film the shop is densely populated by naked female mannequins whose faces are, for no explicable reason, wrapped in foil. It’s a brilliantly visual evocation of my point above, which sets the tone and theme for the rest of the film. But, and here’s the connectivity moment, since I was going to be in the studio anyway, a day or so later, the producer asked me if I wouldn’t mind also joining in a different conversation on the programme – a short engagement with the new Channel 4 Series Humans, as a follow on from discussion with Laurence Scott about his new book The Four-Dimensional Human. So I dutifully sat down to watch the first episode of Humans only to discover that my main problem with it (and there were many problems) was its uncritical engagement with female embodiment. And of course it’s about synthetic humans, animate mannequins. I wonder if my response to Humans would have been different if I hadn’t just reread The Driver’s Seat, or if I hadn’t just discussed the very problem regarding cinematic and televisual representations of AI and women a week or so ago at the Southbank? Possibly. My concern might have been more about the awkward way in which the first episode of Humans stuffs itself with previous SF material without any knowing reference to the wealth of its generic heritage (apart from one now clichéd allusion to Asimov and his laws of robotics). But what most concerned me in the first episode was the uncritical fetishisation of the female robot – which we’ve seen already this year in Ex Machina – and the way in which the episode indulged in anthropocentric navel-gazing rather than a proper and challenging engagement with what I have no doubt will be the radically derailing and thoroughly alien outcomes if scientists ever do produce artificial intelligence to challenge our own. When are male writers and directors going to realise that if they want to push their imaginations into the future, it might be quite helpful to start by reimagining the gender stereotypes and norms of the present? We had the female sexbot over a hundred years ago in Metropolis; please let’s have the creativity to consider that if the singularity does happen, gender is going to be the last thing on the AI’s body or mind.