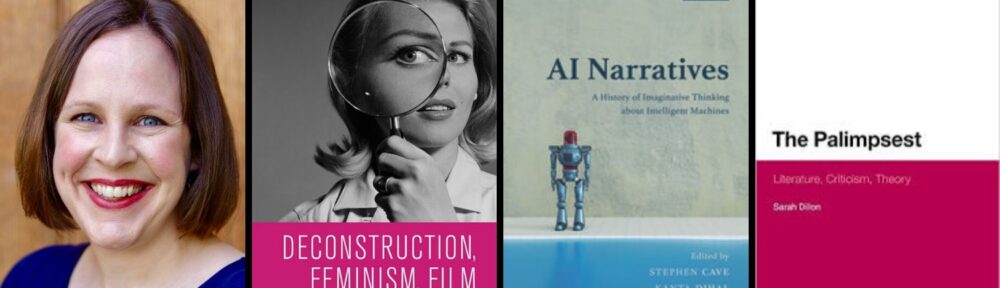

With Deconstruction, Feminism, Film submitted and with it a number of intellectual questions I’ve been wrestling with for over a decade put to rest, I am now delightedly embracing my research on science fiction, and on science and literature. This work began whilst I was at St Andrews and has been bubbling along over the past three years, but it took a back seat to prioritise finishing the film book. Now it gets to take centre stage! Earlier this month, I joined the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence as a Senior Research Fellow and co-Project Lead on the AI Narratives project. I’ll be working alongside co-Project Leads Dr Stephen Cave, Executive Director of CFI, and Claire Craig, Director of Science and Policy at the Royal Society, as well as Kanta Dihal, our postdoctoral researcher and Associate Fellow, Dr Beth Singler. It’s a great team, and an exciting three year project to explore how AI is currently portrayed in literary, cinematic and other cultural narratives, what impact that might be having, and what we can learn from how other complex, novel technologies have been communicated. The Royal Society have also generously funded a more focused reboot of the What Scientists Read research I carried out with a multidisciplinary team in Scotland, so watch this space for updates on the AI Narratives project and on What AI Researchers Read…

Tag Archives: science fiction

And so I’m back, from outer space…

On location, Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, Arizona. A rare moment of getting to hold the kit for a photo op as the roof of the observatory is opened.

After 6 months in solitary academic confinement, and with The Book triumphantly written, the beginning of 2017 has seen me return to life beyond my study with renewed enthusiasm and vigour. I’ve spent the past few months steeped in the Martian imaginings of our greatest writers and scientists for a BBC Radio 4 documentary on mankind’s romance with the red planet, for which I had the great if exhausting pleasure of a weekend trip to Mars’ Earth analogue, Arizona. We visited Percival Lowell’s Flagstaff observatory to learn more about how it all began, and then descended to Phoenix to talk about where we are now, with contemporary Mars scientists at Arizona State University. There may also have been a morning spent barsooming around the Arizona desert – as close to Mars as I’m ever going to get – imagining encounters with magnificent and fearsome six-limbed Tharks. And if that sounds a little frivolous, I can assure you that it was actually very illuminating: standing on red rock, looking across the barren desert to the dust clouds on the distant horizon, it suddenly made sense why that landscape inspired the original literary visionary of Mars – Edgar Rice Burroughs – whose experiences on those plains and encounters with their native inhabitants shaped his Martian imaginings. The programme will be broadcast as part of Radio 4’s Martian Festival at the beginning of March – more details to follow.

I also had the pleasure this week of a stimulating hour’s conversation with SF writers Roz Kaveney and Aliette de Bodard for an episode of Radio 4’s Beyond Belief on religion and science fiction, which will be broadcast on Monday 13th March. And, to knock a little realism into me, next month I’ll start recording my new series of Literary Pursuits by investigating the story behind the story of E. M. Forster’s posthumously published Maurice. Fortunately, neither interplanetary nor transatlantic travel is necessary to get started on that investigation, since a treasure trove of Forster’s papers sits on my doorstep in King’s College Cambridge’s modern archives.

King’s Fantastic Talks Series: Faber

BBC Radio 3 Free Thinking: The Curious Combination of Muriel Spark and Channel 4’s Humans

Before he became famous as the founder of modern structural linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure had this crazy side project looking for anagrams hidden in Latinate poetry, during which time the more he looked for connections, the more he found them. Saussure eventually abandoned the project but there’s a great book by Jean Starobinski called Words Upon Words that presents Saussure’s early research and recounts the story of his obsession. I came across it a long time ago when working on my PhD – and I discuss it in one of the chapters of my first book, The Palimpsest – but it always comes to mind again when unexpected connections present themselves to me. It always makes me wonder, as Saussure did, whether the connections are really there, or whether they are only there because I’m creating them. Over the years, I’ve become convinced that most frequently it is the latter – the connections only exist because you create them. But rather than this predicament leading me to question my sanity, I’m now convinced that this fortuitous and unanticipated connectivity is in fact the lifeblood of intellectual enquiry and, in fact, of any other form of creativity.

What’s prompted me to remember Saussure and his anagrams this week is an invitation I received from BBC Radio 3’s Free Thinking to go on the programme to talk to Rana Mitter, along with Laurie Sansom, about Muriel Spark’s The Driver’s Seat and Laurie’s new adaptation of it for the Scottish National Theatre. Having just reread The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie for my Open Book Close Reading series, it was a pleasure to be prompted to reread another Spark text that I first read in the dim and distant past. It’s a weird and disturbing novella, with a dark side that far exceeds the sinister manipulations of Miss Brodie. Laurie Sansom says that he was prompted to develop the first stage adaptation because it seemed essentially dramatic. And he’s absolutely right: so much of the prose in fact reads like stage directions. This is a novella about setting, actions, and objects, with a third person narrator that knows what happens in the future but has no access at all to what’s inside the female protagonist Lise’s head. As we were talking on the programme, it occurred to me what a radically but problematically feminist text this is – it’s a biting satire on the conventional tropes of woman as victim. It eschews the immersion in psychological complexity of classic texts of female madness such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper. But the control she takes of her own fate – she seeks out and orchestrates her own murder – does not extend to an ability to control her sexual violation. Only through luck does she escape from two attempted rapes, and the man she has selected as her killer rapes her as well, despite her express wishes that his violation remain purely murderous, not sexual. We never find out what’s going on in Lise’s head, and that’s the point – that’s what renders her powerful rather than vulnerable; orchestrator rather than victim. But that power is also continually threatened by the unavoidable vulnerability of her female body. Which makes this a text about women and our bodies – to what extent we can control them and to what extent, whatever the defences we put in place with regard to our minds, we remain vulnerable in our embodiment.

Which leads to the unexpected connection. Giuseppe Patroni Griffi’s 1974 film adaptation of Spark’s novel adheres remarkably closely to the literary original. But it adds a curious uncanny touch in the opening scene – Lise is trying on a dress in a shop, as in the book, but in the film the shop is densely populated by naked female mannequins whose faces are, for no explicable reason, wrapped in foil. It’s a brilliantly visual evocation of my point above, which sets the tone and theme for the rest of the film. But, and here’s the connectivity moment, since I was going to be in the studio anyway, a day or so later, the producer asked me if I wouldn’t mind also joining in a different conversation on the programme – a short engagement with the new Channel 4 Series Humans, as a follow on from discussion with Laurence Scott about his new book The Four-Dimensional Human. So I dutifully sat down to watch the first episode of Humans only to discover that my main problem with it (and there were many problems) was its uncritical engagement with female embodiment. And of course it’s about synthetic humans, animate mannequins. I wonder if my response to Humans would have been different if I hadn’t just reread The Driver’s Seat, or if I hadn’t just discussed the very problem regarding cinematic and televisual representations of AI and women a week or so ago at the Southbank? Possibly. My concern might have been more about the awkward way in which the first episode of Humans stuffs itself with previous SF material without any knowing reference to the wealth of its generic heritage (apart from one now clichéd allusion to Asimov and his laws of robotics). But what most concerned me in the first episode was the uncritical fetishisation of the female robot – which we’ve seen already this year in Ex Machina – and the way in which the episode indulged in anthropocentric navel-gazing rather than a proper and challenging engagement with what I have no doubt will be the radically derailing and thoroughly alien outcomes if scientists ever do produce artificial intelligence to challenge our own. When are male writers and directors going to realise that if they want to push their imaginations into the future, it might be quite helpful to start by reimagining the gender stereotypes and norms of the present? We had the female sexbot over a hundred years ago in Metropolis; please let’s have the creativity to consider that if the singularity does happen, gender is going to be the last thing on the AI’s body or mind.

The Brave New World of Science Fiction Theatre

This week I’ve come over all dramatic, having caught the current buzz around SF theatre. This afternoon I popped down to London to watch the new Headlong production of George Orwell’s 1984 which has just begun its West End run. I have to say I found it a little disappointing. The opening was almost embarrassingly patronising as it gathered together a reading group to ‘teach’ the audience how to understand the novel. But once they got past that, it steadily improved and Mark Arends was subtly convincing in his portrayal of a psychologically damaged, disoriented, if not downright unhinged, Winston. On the train ride home I finished off a new Sci-Fi-London blog on SF theatre, which will appear here shortly. And if I could have been in two places at once, I’d also have sent my avatar over to LA to catch Sci Fest, the first science fiction theatre festival (poster above, and more on them in the blog ) which looks nothing less than tremendous. All in all, a satisfyingly science fictionaly theatrical day!

Free Thunk!

So, I am all Free Thunk! What a fantastic weekend in Gateshead with the BBC team and my fellow New Generation Thinkers. Speed dating was a heady, super-charged, intellectual comedy with the lovely Ian McMillan hooting the hooter in his own inimicable style. I came runner up each day with my idea that we should have a National Fool to keep us all honest! In slightly more serious proceedings, my discussion of Zamyatin’s dark dystopia We and the contemporary issues we are all facing around surveillance and questions of privacy, security and freedom was broadcast last night on BBC Radio 3. I was lucky enough to participate alongside a trio of the best in the business – David Aaronovitch, Sean O’Brien and Matthew Sweet. If you didn’t catch it last night, you can listen again here.

And here’s me trying to win over the love and votes of the Speed Dating public!